Peeking into the neural network architecture used for Google's Neural Machine Translation

November 17, 2016

The Google Neural Machine Translation paper (GNMT) describes an interesting approach towards deep learning in production. The paper and architecture are non-standard, in many cases deviating far from what you might expect from an architecture you'd find in an academic paper. Emphasis is placed on ensuring the system remains practical rather than chasing the state of the art through typical but computationally intensive tweaks.

The architecture

To understand the model used in GNMT we'll start with a traditional encoder decoder machine translation model and keep evolving it until it matches GNMT. The GNMT evolution seems primarily motivated by improving accuracy while maintaining practical production speeds for both training and prediction.

V1: Encoder-decoder

The encoder decoder architecture started the recent neural machine translation trend. I'd refer to it as old school if it were more than a few years old. Shockingly, as the name implies, there are two components - an encoder and a decoder.

For a word level encoder-decoder machine translation system, such as the depiction below:

- Take an recurrent neural network (RNN) - usually an LSTM - and encode a sentence written in language A (English).

- The RNN spits out a hidden state, which we refer to as S.

- This hidden state hopefully represents all the content of the sentence.

- This hidden state S is then supplied to the decoder, which generates the sentence in language B (German) word by word.

The encoder decoder showcased the potential that neural based machine translation may provide. Even with modern complex neural machine translation architectures, the majority of them can still be decomposed in terms of the encoder-decoder architecture.

There are two primary drawbacks to this architecture, both related to length. First, as with humans, this architecture has very limited memory. That final hidden state of the LSTM, which we call S, is where you're trying to cram the entirety of the sentence you have to translate. S is usually only a few hundred units (read: floating point numbers) long - the more you try to force into this fixed dimensionality vector, the more lossy the neural network is forced to be. Thinking of neural networks in terms of the "lossy compression" they're required to perform is sometimes quite useful.

Second, as a general rule of thumb, the deeper a neural network is, the harder it is to train. For recurrent neural networks, the longer the sequence is, the deeper the neural network is along the time dimension. This results in vanishing gradients, where the gradient signal from the objective that the recurrent neural network learns from disappears as it travels backwards. Even with RNNs specifically made to help prevent vanishing gradients, such as the LSTM, this is still a fundamental problem.

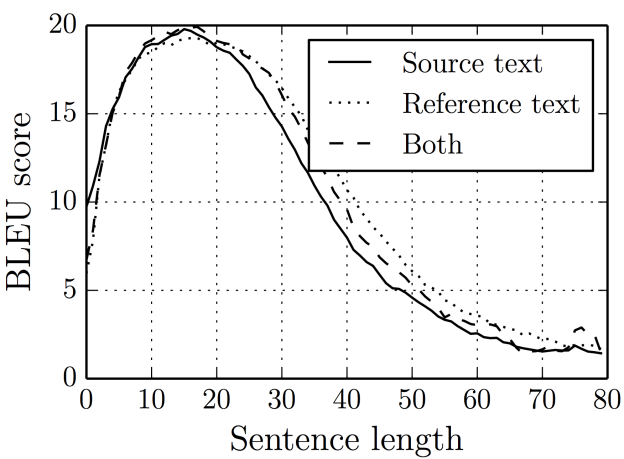

Caption: Image from Bahdanau et al.'s "Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate" (2014) showing the impact on translation scores (in the form of BLEU scores) as sentences get longer.

While it may work for our relatively short example above, it's likely to begin failing as the sentence gets longer. One obvious solution for the memory problem would be increasing the hidden size of the LSTM. Unfortunately, training rapidly becomes impractical if we do this. As you increase the hidden size h of the LSTM, the number of parameters increases quadratically! You'll either start running out of memory on your GPU or have training take an eternity. This also doesn't solve the vanishing gradient problem...

V2: Attention based encoder-decoder

How do we solve these problems? We might try turning to a technique humans naturally perform - iterative attention to relevant parts of the source sentence. If you were translating a long sentence, you'd likely glance back at the source sentence to ensure you're capturing all the details. We can allow neural networks to do exactly the same. By storing and referring to the previous outputs of the LSTM we can increase the storage of our neural network without changing the operation of the LSTM. Additionally, if we know we're interested in a particular part of the sentence, the attention mechanism acts as a "shortcut" so we can provide a supervision signal that doesn't have to traverse the large number of timesteps that would result in a vanishing gradient. This is akin to how a human might answer a question after having just finished reading all of Lord of the Rings. If I was to ask a specific question about the start of the story, at Bag End, a human would know where to flick open the first book and retrieve the answer from. The length of the book series doesn't impair your ability to perform that lookup.

Briefly (as attention mechanisms are already well covered elsewhere) the idea is, once you have the LSTM outputs from the encoder stored, you query each output asking how relevant they are to the current computation on the decoder side. Each output from the encoder then gets a score of relevance which we can turn into a probability distribution that sums up to one via the softmax activation. We can then extract a context vector that's a weighted summation of the encoder outputs depending on how relevant we think they are.

A drawback to the attention mechanism is that we now have to perform a calculation over all of the encoded source sentence for each and every output of the decoder. While this is likely fine for translating between sentences, it can become problematic for long inputs. In computing terminology, if your source sentence is of length \(N\) and your target sentence of length \(M\), we've just take the decoder from \(O(M)\) in the encoder-decoder architecture to \(O(MN)\) in the attention architecture. While not optimal the advantages of the attention mechanism far outweigh the disadvantages, at least for this task.

Note: You may notice that the direct connection between the encoder and decoder (S in our previous architecture) has disappeared. While many standard encoder-decoder architectures maintain this direct connection, the GNMT architecture decides to remove it. The GNMT architectures decides to make the attention mechanism the only way that information can be shifted from the encoder side to the decoder side.

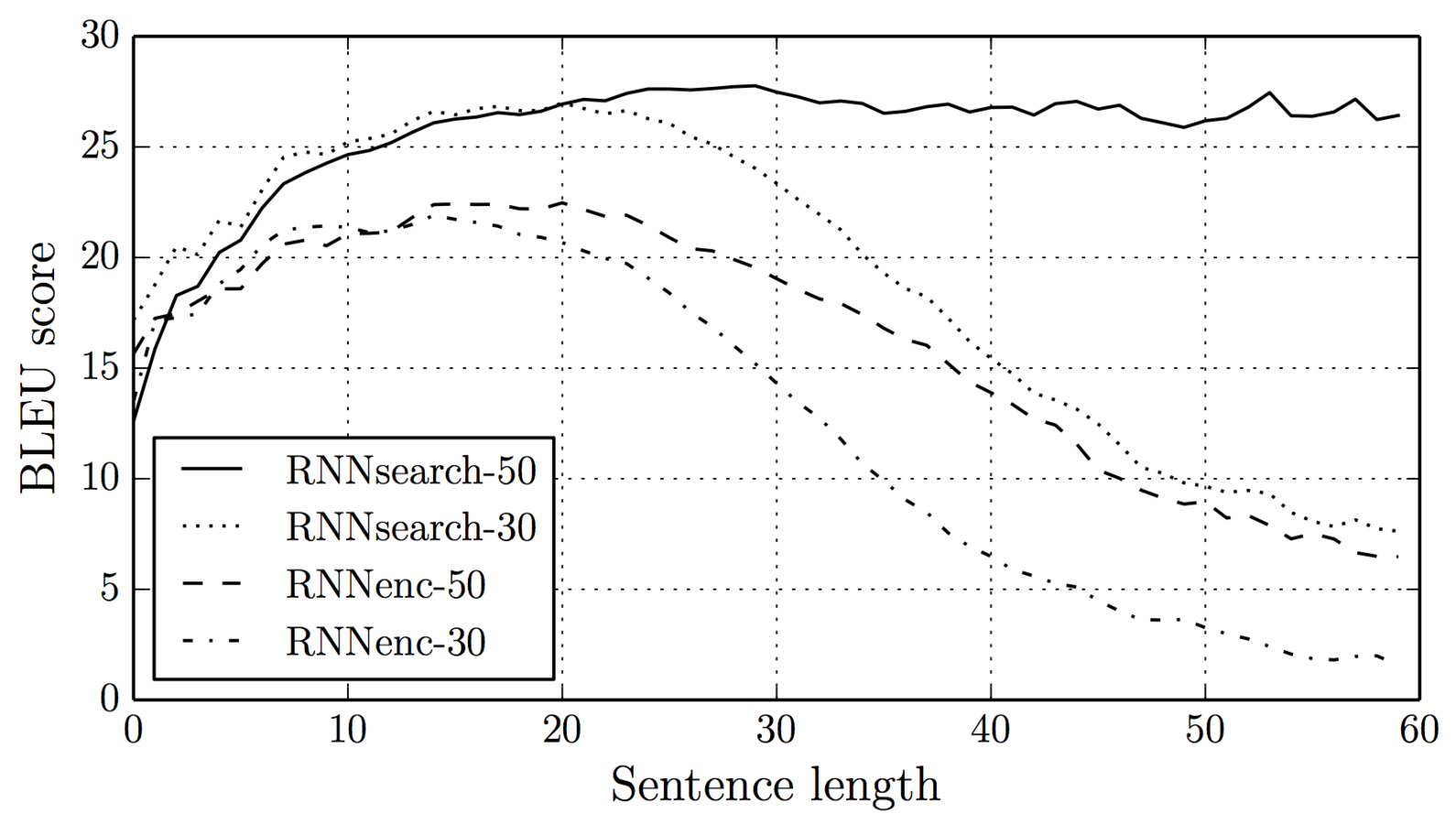

Caption: Image from Bahdanau et al.'s "Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate" (2014) showing the impact on translation scores (in the form of BLEU scores) when using attention. RNNsearch is the architecture with attention and the number afterwards indicates how long the training examples were.

V3: Bi-directional encoder layer

While the attention mechanism allows for retrieving different parts of the sentence depending on the decoding context, there's still an issue. The attention mechanism is essentially asking the stored outputs of the encoder "are you relevant to this?" and using that to determine what information to extract. If the encoder outputs don't have sufficient context themselves, they're unlikely able to provide a good answer.

Adding information about future words, such that the encoder output is determined by words on both the left and the right, is clearly beneficial. If a full sentence is available, humans would almost certainly use the full context to determine the meaning and context of a word. Why would we force computers, who are already at a substantial handicap, to not use all available information?

The easiest way to add this bi-directionality is to run two RNNs - one that goes forward over the sentence and another that goes backwards. Then, for each word, we can either concatenate or add the resulting vector outputs, producing a vector with context from both sides. A bi-directional encoder becomes even more important if you're translating to or from a language that has a different ordering (i.e. right-to-left). The GNMT architecture concatenates them - potentially advantageous as that results in the both the forward and backward RNN being only half the size. Given that the bi-directional layer ends up being a bottleneck in GNMT, and the number of parameters in an RNN scale quadratically, this is not an insignificant saving.

V4: "The deep is for deep learning"

For many architectures in neural machine translation, increased depth is a key component in accurate models. The GNMT architecture trends this direction too by adding a large number of layers. A pretty darn crazy large number of layers - 8 on the encoder and 8 on the decoder for 16 total. Many state of the art machine translation systems use far less than this.

For the encoder, their model has one bi-directional RNN layer followed by seven uni-directional RNN layers. The decoder has eight uni-directional RNN layers.

In most papers I'd have instead expected all of the layers to be bi-directional for improved accuracy. A model with all bi-directional layers would be expected to get the same or higher results. The next section explains why the GNMT model variant strayed away from this.

Recurrent neural networks of this depth are highly problematic to train. Indeed, standard neural networks of this depth are not trivial to train either, and those are relatively simple compared to what happens over the many timesteps. We'll look to solve this problem in a later variant.

V5: Parallelization

A primary motivator for the GNMT architecture was practicality. This forces some limitations and odd choices when compared to standard encoder-decoder architectures. For launching a system like GNMT into production, being parallelizable is a requirement. It makes not only training faster, allowing more experiments, but also makes production deployments faster too.

The graph we've been looking at represents not only the architecture of the machine translation model but also a dependency graph. To begin computation at one of the nodes, all of the nodes pointing toward you must already have been computed. Even if you had an infinite amount of computation, you still need to follow the flow of the dependency graph. As such, you want to minimize any dependencies that may take far more computation than others at a similar level.

Note: Unshaded nodes have not yet been completed and nodes shaded white have finished their computation. Layers shaded blue are in the process of being computed or have finished being computed.

This is the reason that only a single bi-directional RNN layer is used.

A bi-directional layer has to run two RNNs - one from left to right and the other from right to left.

This means to compute the first output you have to wait for N computations from the far right hand side to reach you (where N is the length of sequence).

If all layers were bi-directional, the entirety of that layer would have to finish before any later dependencies could start computing. If we use uni-directional layers however, our computations can be more flexible and more parallel. In the example above, focusing just on the encoding side, the first four layers are all computing nodes at the same time. This is only possible as the layer above doesn't rely on all of the nodes in the layer below, only those directly below it. This would not be possible if these were bi-directional layers.

Parallelization (decoder side): Due to the attention mechanism using all the outputs of the encoder side, the decoder side must wait until all of the encoder has finished running. When the encoder has finished however, the decoder can perform its operations in the same parallel way as the encoder side. Usually the attention mechanism would use the top most output of the decoder to query the attention mechanism but the GNMT architecture uses the lowest decoder layer for querying the attention mechanism to minimize the dependency graph and allow for maximal parallelization. In the example above, if we used the topmost decoder layer for attention, we would not have been able to start computing the second output of the decoder yet, as the first output of the decoder is still in progress.

Side note (teacher forcing and training vs production): During training, we already known what the English sentence should translate to. This allows us to have higher levels of parallelism than at prediction time. As we already have all of the correct words (the "known" translation at the bottom right), we can use it in teacher forcing. Teacher forcing is where you give the neural network the correct answer for the next word even if it would have actually guessed the wrong word. This makes sense as training will keep forcing the network towards outputting the correct word, so eventually our assumption should hopefully be correct. This allows you to "cheat" and be computing the second output word while still in the process of computing the first output word. In the real word, we need to wait to produce each word one by one, as there's no "known" translation.

Side note (multiple GPUs): This parallelization really only strongly makes sense with multiple GPUs. In the GNMT paper, their diagrams actually label each of the layers according to the GPU they use. For the encoder and decoder, they use eight GPUs - essentially one for each layer. Why doesn't this make as much sense for a single GPU? Generally a GPU should be hitting high utilization when computing a given layer, assuming you're able to set reasonable batch sizes, network sizes, and sequence lengths. This work is primarily about re-ordering dependencies such that more computation can be done at once, allowing for better utilization of more devices. You're hopefully already fully utilizing your single GPU well, so being able to compute more at the same time won't help you if you don't have that computation spare. If the production deployment was on CPUs, this re-ordering may still be quite beneficial.

V6: Residuals are the new hotness

Eight layers is pretty darn deep - at least for recurrent neural networks. Returning to our general rule of thumb - barring some exceptions or specific constructions - the deeper a network is, the harder it is to train. While this is for a variety of reasons, the most intuitive is that the further a gradient has to travel, the more it risks vanishing or exploding. Luckily there are many potential ways to tackle this problem.

One solution for vanishing gradients is residual networks, which has been applied most famously to CNNs such that training neural networks hundreds of layers deep remains feasible. The idea is relatively simple. By default, we like the idea of a layer computing an identity function. This makes sense. If you do well with one layer, you don't expect a two or three to do worse. At worst, the second and third layer should just learn to "copy" the output of the first layer - no modifications. Hence, they just need to learn an identity function.

Unfortunately, learning the identity function seems non-trivial for most networks. Even worse, later layers confuse training of earlier layers as the supervision signal - the direction it's meant to go - keeps shifting. As such, the first layer may fail to train well at all if there are more layers below it. To solve this, we bias the architecture of each of these layers towards performing the identity function.

We can do this by only allowing the later layers to add deltas (updates) to the existing vector. Now, if the next layer is lazy and outputs nothing but zeroes, that's fine, as you'll still have the original vector.

$$ \text{Starting by processing } x \\ h_1 = f_1(x) + x \\ h_2 = f_2(h_1) + h_1 = f_2(h_1) + f_1(x) + x \\ h_3 = f_3(h_2) + h_2 = f_3(h_2) + f_2(h_1) + h_1 = f_3(h_2) + f_2(h_1) + f_1(x) + x \\ h_3 = x + \delta_1 + \delta_2 + \delta_3 \\ \text{(if all values for }\delta\text{ are zero, we still end up with } x \text{)} $$

The GNMT monster in its full glory (more or less)

All of these changes build upon their previous iteration to result in the full architecture described in the GNMT paper. Notice that, while far more complex, it still has the same components of the original encoder-decoder architecture. It may look scary, but each change is motivated by a relatively simple idea.

Conclusion

The Google Neural Machine Translation architecture is an interesting beast. While there's nothing tremendously novel in it, the real innovation is the care to which the architecture has been engineered. If this was a boat, it'd be a chrome speed boat that slices through rough waters with near zero drag. We're already seeing the architecture used in a variety of contexts, both in translating and generating natural language, likely due to the ability to scale to computationally large and intensive tasks cleanly. For that reason, I expect to see it pop up in far more places.

This article also contains only a small portion of the paper. Not discussed here is what BLEU is, how wordpiece level granularity improves translation over word level, advantages/disadvantages of BLEU, quantization of models for faster models during deployment, or jumping between optimization algorithms for better convergence, or that their datasets are so large they don't use dropout! All of this without mentioning the zero-shot GNMT paper or using the GNMT architecture for conversation models...

Gosh there's a lot to write about!

If you like this content, I share similar things on Twitter a few hundred characters at a time ;)

My sincere thanks to:

- James Bradbury, who implemented the world's second best neural machine translation system for English to German while only an intern at Metamind, and who happily induldges me when I harass him for details :)

- Denny Britz, who was happy to clarify some questions I had regarding my reading of the GNMT architecture paper and gave early feedback on the article itself - check out his articles at WildML!

- Jonathan K. Kummerfeld for his read through and suggestions. Among other things, turns out my brain thinks "direction connection" should be amalgamated to "direction" ;)

Popular Articles

- It's ML, not magic: machine learning can be prejudiced

- It's ML, not magic: the rise of AI-prefix investing

- In deep learning, architecture engineering is the new feature engineering

- How Google Sparsehash achieves two bits of overhead per entry using sparsetable

- Where did all the HTTP referrers go?

Interested in saying hi? ^_^

Follow @Smerity