Password Security: Why salting with usernames is no good

June 7, 2012

LinkedIn recently lost 6.5 million password hashes, prompting an interesting discussion on Hacker News about the implications of such a leak. LinkedIn suffered from two fundamental issues: no protection against rainbow tables in the form of a salt and no protection from brute force attacks due to the easy computation of plain SHA-1.

In the Hacker News discussions, the idea of employing the username as a salt was raised numerous times. The standard response is "don't do that, just use bcrypt".

What I want to illustrate is how decisions in security that seem logical can result in new vulnerabilities being introduced.

This whole story is to emphasise the old adage of "don't re-invent the wheel when it comes to security"

For example, bcrypt is well audited, supports numerous languages, features protection from rainbow tables via random salts and protection from brute force via key stretching.

All these benefits are added with no extra work on the part of the programmer.

A Pinch of Salt

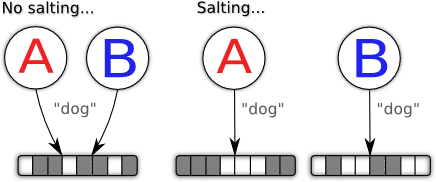

In password hashing, a salt consists of a collection of random bits that are used whilst hashing a user's password. As the salt is different for each user, it means that even if users A and B have the same password, their resulting password hashes will be different.

This function of salts protects password hashes against rainbow tables, which allow an attacker to quickly crack password hashes with a high probability after spending a large amount of time constructing the rainbow table. How likely a password hash is to be cracked can be set by adjusting both how much CPU time and how much storage the rainbow table is allowed to use. Most importantly, however, once this rainbow talbe is constructed it can be re-used for as many password hashes as the attacker would like.

Vital point for later: Random salts help protect against rainbow tables.

Without salting, someone can trivially work out how commonly passwords are re-used just by counting the times a password hash occurs. For example, League of Legends "discovered that 11 passwords were shared by over 10,000 players each". This is only possible if their password hashing scheme didn't involve salts.

The Username as a Salt

A common suggestion on Hacker News was "why not just use the username as a hash instead of a random salt?". This was usually suggested as it meant not having to store the salt.

To be honest, storing the salt is trivial however and shouldn't be considered an issue.

bcrypt for example stores the salt in the password hash itself,

in the form of $ algorithm $ cost factor $ 22 characters of salt | 31 characters of hash.

Whilst it initially sounds like a good idea, salting with a username results in a serious issue: predictability of the salt. Let's see what we can do with this exploit.

Exploiting the Username-Salt Vulnerability

Imagine a scenario where a system was secured and the savvy users are warned and change their passwords within two hours.

Sadly, this is an incredibly optimistic scenario.

What might be more likely is that the company will prevent logins to leaked user accounts within two hours of some internal security warning being triggered.

LastPass, for example, disabled logins from new IPs and requested master passwords changed soon after they detected traffic patterns in their network that they couldn't account for.

Note that they didn't confirm their system had been compromised before taking this action.

This means the attackers would have had to act incredibly quickly to take advantage of their theoretical breach.

As in the TV show The First 48, the successful use of leaked password information would be most likely in the first n hours after the break in. This is assuming that (a) the company reports the break in to impacted users promptly and (b) the user changes their password soon after this announcement or (c) logins from previously unused IPs require additional authentication before they're allowed.

Note: I have no statistics to back this assertion up -- statistics about security incidents are few and far between for obvious (embarassing) reasons. Very few companies and users react to a new security incident in less than one or two hours however. Some take years... ಠ_ಠ

If the password hashes are unsalted, then one can simply download pre-made rainbow tables for common hash algorithms (LM hash, MD5, SHA-1, etc). Breaking thousands of user passwords can be done in a matter of seconds with high probability.

The reason salting was added was to prevent this very attack and give users time to respond to the security leak.

Using the 'usernames as salts' password scheme results in a significant vulnerability for targeted users. To defeat a salt based on usernames:

- Find a set of high value targets (

larrypage,markzuckerberg,billgates, ...) - Pre-compute a rainbow table with the salt set as

usernamefor each of the users

These rainbow tables can be generated over as long a period as the attacker desires and the longer they spend the higher the probability that a targeted user's password will be broken. Only once these rainbow tables have been generated would the attacker strike.

- Compromise the target system and retrieve the password hashes

- Alarm triggered -- assume one or two hours before either:

- logins from new IPs are no longer allowed or

- users are forced to reset their master passwords

- Use the pre-generated rainbow tables to reveal the target user's password with high probability

- Take advantage of their accounts in the remaining time

By using usernames as salts, we provide attackers with enough information ahead of time to weaken the system's security. With random salts, work to crack the password hashes can only begin after the target system has been compromised.

Whilst the situation will be better for the standard user, it will be no better for targeted users. As seen in the recent Linode security incident, targeting specific users can still be profitable to the tune of thousands of dollars! Additionally if this became common practice then the per-user rainbow tables will become useful across multiple sites -- obviously not something that is desired.

Note that this attack is only possible as the salt is not random and instead a known piece of information.

Conclusion

Whilst you might say this scenario seems unlikely, it's no less unlikely than some recent attacks that have been carried out using "unlikely" tactics.

Most importantly, this security flaw would only be possible due to a programmer making a small mistake. These small mistakes can result in substantial security vulnerabilities as seen with the Debian SSL keys incident. The best suggestion is to use a pre-exising and well audited password hashing library and to avoid re-inventing the wheel yourself!

Popular Articles

- It's ML, not magic: machine learning can be prejudiced

- It's ML, not magic: the rise of AI-prefix investing

- In deep learning, architecture engineering is the new feature engineering

- How Google Sparsehash achieves two bits of overhead per entry using sparsetable

- Where did all the HTTP referrers go?

Interested in saying hi? ^_^

Follow @Smerity