Cython - making Python high and low level

February 25, 2018

Python is the work horse for much of machine learning - but it can be slow when not gluing together fast, black box low level components. How can we fix that, transparently, with Cython?

Python is the work horse for many data scientists and machine learning practitioners. This is thanks not just to the quality of the language itself but also the healthy ecosystem that has built up around it. Libraries and frameworks such as Numpy, Scikit-Learn, pandas, TensorFlow, PyTorch, and Chainer/cupy enable massive productivity on computationally expensive and challenging tasks.

For both the language and these libraries, a common pattern is to implement the computationally expensive work using a lower level language such as C. The standard implementation of Python, CPython, has its namesake for this very reason.

When a programmer uses a dictionary in CPython or performs a matrix multiplication in Numpy, their request is actually transparently sent deep down the stack to highly optimized C code. For most tasks, the combination of speed and simplicity is perfect. Python acts as a high level glue language orchestrating operations written in low level compiled code.

What happens when we move away from that sweet spot however? What happens when that high level glue needs to be used everywhere? The overhead of running relatively simple commands in Python becomes the performance killer. This isn't a problem when it's a large matrix multiplication for a neural network, the majority of the compute time spent in parallel computation on the GPU, but it is if you have many small calls.

So exactly how can we save ourselves from that disaster? How can we replace that glue with bare metal?

Meet Cython

Cython is a magical helper that will take your Python code and invisibly convert what it can to compiled C. Sounds too good to be true? I don't blame you - but it really can be that good.

Cython provides the easiest way to write and integrate C code with CPython whilst avoiding the majority of the headache. The C code is literally generated for you. By default you can throw many Python scripts at it and see some benefit. If you're willing to annotate and nudge Cython to be smarter, you are likely to see major speed improvements.

The best example of this mad mix in the machine learning may be the spaCy library. My friend Matthew Honnibal seemed obsessed with (and quite successful at) squeezing stunningly good performance out of Python. Cython - and his annoyingly brilliant brain - were key to this. If you're interested, check out spaCy for an example of using Cython to make NLP insanely efficient in Python!

"Both the Cython version and the C version are about 70x faster than the pure Python version, which uses Numpy arrays."

-- Matthew Honnibal, Writing C in Cython

"Just use a compiled language!" I hear someone shout from the back

If you use a different language, you're making many tradeoffs. The reason you're likely using Python is not just as it's lovely and high level but also as it has a rich ecosystem. By shifting away from Python, you may lose one or both of these.

Instead of shifting away from Python, you may elect to write the computational intensive code in another language. This unfortunately makes many things far more complicated. Using Python and calling to your foreign code means you and your team need to use and be familiar with two or more languages. You and your team will also need to carefully decide on which parts of the codebase to convert to the low level language - every conversion means more and more plumbing code as information is shipped back and forth between the languages.

Cython allows for a slow and gradual shift towards a lower level language without the plumbing or dual language overhead. If you find this isn't enough, nothing stops you from going the FFI route if that's what necessary - but Cython will likely allow you to stay in the single language oasis longer. Finally, Cython will help prevent you from performing premature optimization when it isn't necessary as it provides useful tools to inform you where overhead is likely occurring.

An example of Cython gotchas

- You likely need to know the basics of C if you want the stronger optimizations or sanity during debugging

- When you make Cython optimizations, it opens up bugs that CPython would traditionally protect you from (i.e. integers will never overflow in CPython as they have unlimited precision)

- Slight surprise on certain C'isms (

lenbeing called each time in C/Cython rather than being cached as in Python by default,unsigned char *suddenly cares about NULL bytes when runninglen) - Bonus points if you can read CPython style C happily (though you'll likely be able to pick it up in real time)

Simple task: counting byte frequency

Imagine you had a large file and wanted to (a) count the frequency of certain bytes (i.e. how many times A appeared) and (b) sum all the byte values.

Whilst that's a relatively simple task, the Python overhead for simple operations can be a performance killer.

Luckily for this task Python has built-ins that are well optimized that are fit for the task.

We'll be using those for the CPython baseline.

In many other situations however we may not be that lucky...

We'll explore how Cython is able to optimize three different small Python snippets, with each optimization strategy dictated by the Python data structure used. The data structures are a default dictionary, an array, and a counter.

The counter strategy

The counter strategy is the simplest in terms of Python code.

We use Counter to find the byte frequency and a separate sum(data) to calculate the total.

Both of those are well optimized by CPython with the majority of the work taking place in compiled C code.

def sumBytes(data): total = 0 d = Counter(data) total = sum(data) return total, d

The counter strategy is not only fast but it's simple. We're lucky in this case that our task is a perfect match for the optimized built-ins that Python supplies for us. As the majority of the workload is already optimized C code, and Python code does almost nothing here, Cython's impact is negligible. Bad luck Cython.

| Data Structure | Raw in Python | Raw in Cython | Cython annotated | Cython optimized |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counter | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | - |

| Dictionary | - | - | - | - |

| Array | - | - | - | - |

The dictionary strategy

The dictionary strategy is conceptually almost identical except that we perform the work that Counter(data) would have done in a Python loop.

We iterate over the data byte by byte adding the counter to a default dictionary (i.e. a dictionary that has a default value when the key has not been used before).

Generally whenever you have "slow code" in your inner loop, such as "grab byte, add one to the count of that byte in the dictionary" written in Python, you're in trouble.

Let's see how Cython handles this.

# This version is raw Python / raw in Cython def sumBytes(data): total = 0 d = defaultdict(int) for i in range(len(data)): total += data[i] d[data[i]] += 1 return total, d # This version is Cython annotated # - We note that data is an unsigned character array # - We note that total and i will be integers in C def sumBytesAnnotated(unsigned char *data): cdef long int total = 0 ### d = defaultdict(int) for i in range(len(data)): total += data[i] d[data[i]] += 1 return total, d

For the dictionary strategy, we can see the major penalty we pay for Python overhead on the many small operations.

Executing the exact same code after Cython has compiled it to C, however, we see quite a speedup.

This is as the produced Cython C would likely be quite similar to the C written for CPython's counter.

The final opportunity for speedup with Cython is to annotate our variables with their type.

By telling Cython that the input is an array of bytes and that our total will be shorter than a long int, we're able to achieve the same timings as the CPython counter strategy.

| Data Structure | Raw in Python | Raw in Cython | Cython annotated | Cython optimized |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counter | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | - |

| Dictionary | 21.5 | 9.7 | 6.5 | - |

| Array | - | - | - | - |

This result is already a pleasant surprise.

Whilst all we've done here is recreate what can be done with the CPython Counter built-in, not all of our tasks will line up as well with the set of existing CPython built-ins.

This provides the opportunity to get the same types of speed whilst writing plain Python rather than calling out to a separate language.

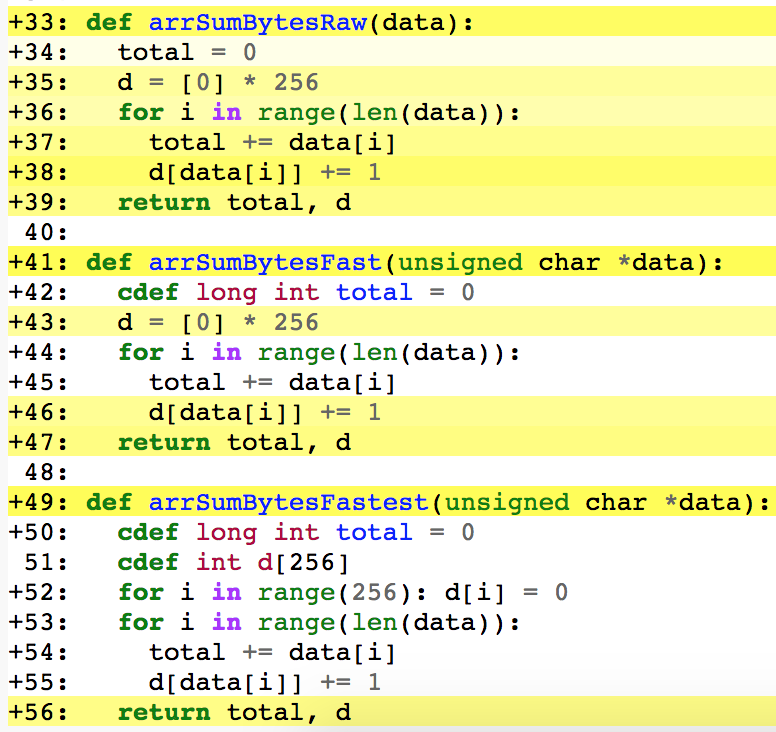

The array strategy

The array strategy is closest to what you might see in C. Like the dictionary strategy above, we loop through the entire file by grabbing a byte at a time and adding one to the count for that byte in our array. Whilst using a fixed size array is not a strategy that's possible for all frequency counting tasks, we can use it here as there are only 256 different byte values we need to worry about.

# This version is raw Python / raw in Cython def sumBytes(data): total = 0 d = [0] * 256 for i in range(len(data)): total += data[i] d[data[i]] += 1 return total, d # This version is Cython optimized # - We note that data is an unsigned character array # - We note that total will be a long int in C # - We create a C array of integers that removes all CPython overhead def sumBytesOptimized(unsigned char *data): cdef long int total = 0 cdef int d[256] for i in range(256): d[i] = 0 ### for i in range(len(data)): total += data[i] d[data[i]] += 1 return total, d

Saving the best for last, the array strategy doesn't give any advantage over the dictionary strategy when it's raw Python. When running the same code in Cython, it's slightly better. With the exact same type annotations as seen in the dictionary strategy, the array strategy is suddenly far faster than the counter or dictionary strategy. The real magic comes when we use just a little bit of C knowledge...

| Data Structure | Raw in Python | Raw in Cython | Cython annotated | Cython optimized |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counter | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | - |

| Dictionary | 21.5 | 9.7 | 6.5 | - |

| Array | 21.3 | 8.9 | 2.3 | 0.1 |

In the inner loop of our Cython, using a CPython list as an array means calling to CPython for each and every byte.

The CPython list is written to be general, capable of holding any type of Python object and adhering to all the (good) complexities of CPython.

The value that's stored in this list is also a CPython integer, which means there's far more overhead than an "unboxed" integer.

If we discard this CPython list and use a raw C array of integers, we no longer have to interact with CPython at all for our inner loop.

All that was required to get this speedup was two lines: cdef int d[256] to declare an array of integers and for i in range(256): d[i] = 0 to ensure they're all zero.

Whilst that does rely on a little C knowledge, it's really not that much for the gains we get!

How do you work out the performance bottlenecks?

The performance bottlenecks when using Cython are almost always where Cython has to interact with CPython land. Examples of this include:

- When you're using a Python integer rather than a C integer - Python integers are far more heavy and also have far more checks

- If your Cython code needs to check that a Python object isn't None on every loop

- When you're placing a C integer into a Python datastructure which requires converting the C integer into a Python integer

- ...

Luckily, Cython has an annotate option that will tell you, line by line, where the performance hotspots likely are.

By running cython --annotate byter.pyx we can see:

This is the Cython annotation for the three array strategy variants: raw, annotated, and optimized. The lines which are the strongest yellow are those with the most CPython interactions. Note that the fastest version has no yellow in the main loop (lines 53 to 55). All work is done in C and then the results are converted to Python objects at the end (line 56).

Even the simplest tactic of minimizing blocks of yellow can pay dividends.

For each line you can also see the CPython C code that has been generated by clicking the plus at the start of the line.

If you can read that generated code, you can also see where there may be specific checks (such as "is this Python object None?" or "does this array access obey bounds checking?") which can be optimized or avoided.

Extra: The real world task of LZP compression

I decided to actually try Cython when playing with old school compression recently. I wanted to implement LZP: a cute, simple, and fast byte-level compression algorithm that's a variant of LZ77 and LZ78, the basis of compression in GIF/PNG/ZIP. When I write for fun, I generally prefer Python as it's the pseudo-code programming language running inside my brain. Unfortunately, compression algorithms generally work at the byte or bit level - a no-go for Python as the per-call overhead can be crippling for large files.

The general idea is that we should copy data from the past when it occurs again in the future.

LZP keeps track of recent prefix patterns we've seen (http if we're using a set of four characters for our match) and if the following characters in the past are the characters we want in the future, we just tell the algorithm to copy the number of matching characters.

As an example, imagine we were compressing:

http://smerity.com/articles/2017/bias_not_just_in_datasets.html http://smerity.com/articles/2017/mixture_of_softmaxes.html

We could instead compress it to:

http://smerity.com/articles/2017/bias_not_just_in_datasets.html http<COPY 29>mixture_of_softmaxes.html

The trick to LZP is that unused byte values tell you when to copy from the past and also how many to copy.

When I had a working Python version, I knew that it'd be slower than I'd wanted, especially given the primary advantage of LZP is that it was fast and memory efficient. I wasn't surprised by this and wanted to investigate Cython as a solution. After a few minutes of fiddling, I had a vastly faster setup.

For compressing the enwik8 dataset, which is 100 million bytes of an English Wikipedia XML dump:

| Raw in Python | Raw in Cython | Cython annotated | Cython optimized | C++ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed (secs) | 256 | 169 | 90 | ? | 20 |

The Python version went from 13 times slower to only 4.5 times slower than a reference C++ implementation. This isn't even a fair fight as the Python implementations use a different and slower data structure internally for finding the matches. Rather than using hash indexing into a fixed array for finding pattern matches, the Python version uses an explicit dictionary, achieving better compression though worse speed and memory utilization. If I rewrote the code now specifically for Cython, and using the exact approach as in the C++ version, I'd expect to match the speed of the C++ implementation.

That I could match C++ speeds from the comfort of my Python code brings a helluva smile to my face :)

This ain't the end of the road

Whilst our example might be a relatively simple task, these speed gains can be found converting real code to Cython. spaCy shows what is possible if you architect your entire codebase around Cython - but most projects don't need that. Most projects are likely happy with Python for almost everything except that one thing. Whenever you find yourself sitting and waiting on a dialog bar, maybe you should be asking yourself if a dose of Cython is the right way to go. It really can give you superpowers when you need it.

Popular Articles

- Backing off towards simplicity - why baselines need more love

- Peeking into the neural network architecture used for Google's Neural Machine Translation

- It's ML, not magic: machine learning can be prejudiced

- It's ML, not magic: the rise of AI-prefix investing

- In deep learning, architecture engineering is the new feature engineering

- How Google Sparsehash achieves two bits of overhead per entry using sparsetable

- Where did all the HTTP referrers go?

Interested in saying hi? ^_^

Follow @Smerity